A greenhouse gas (GHG) inventory is the annual process of cataloging GHG emission sources and quantifying the GHG they emit. The most common greenhouse gases are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and various fluorinated gases (HFCs, PFCs, NF3, & SF6).

Inventorying GHG emissions for a healthcare system is a complex and challenging process. Yet understanding the volume of your organization’s GHG emissions is key to developing effective mitigation strategies. Done well, these mitigation strategies benefit your organization in multiple ways. Shrinking your carbon footprint, lowering energy costs, and releasing fewer pollutants into your local communities can help your organization improve its sustainability and potentially reduce the cost of care.

GHG inventory data illustrates how your institution is fulfilling its moral obligation to “do no harm” by working to reduce harmful emissions into the atmosphere. The global healthcare industry emits 4.4% of global net emissions; that would make it the fifth largest emitter on the planet if it were a country. The US industry is responsible for about 25% of those emissions. The hard data GHG inventories provide is essential as the industry’s emissions come under greater scrutiny.

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) climate pledge requires providers to publicly share their progress on reducing emissions and to inventory their Scope 3 emissions by 2024. HHS and its Office of Climate Change and Health Equity also may develop more formal climate metric requirements. Healthcare providers can be better prepared to understand how these regulations could affect them when they have a clear picture of their own GHG emissions.

Fortunately, a blueprint for GHG inventorying exists — GHG Protocol Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard. As its name indicates, this standard was developed for corporate operations. In this article, we’ll highlight relevant details for healthcare providers to consider as they apply the Protocol to their unique situations.

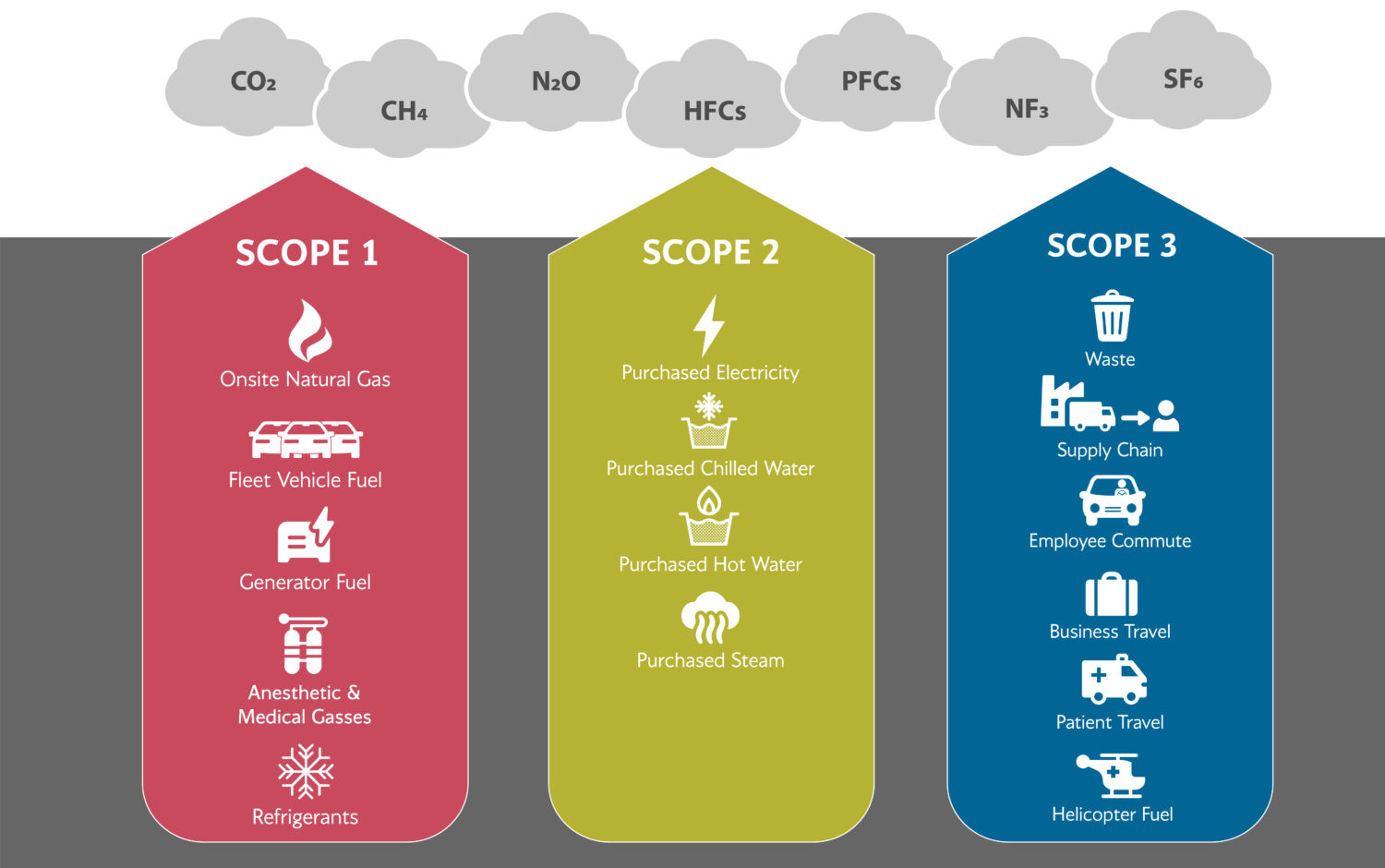

Greenhouse Gas Protocol Emissions Categories

Scope 1 – Direct emissions from fossil fuels burned on site or in owned and operated vehicles.

Scope 1 – Direct emissions from fossil fuels burned on site or in owned and operated vehicles.

Healthcare examples:

- On-site natural gas

- Fleet vehicle fuel

- Generator fuel

- Medical gases

- Anesthetic gases

- Refrigerants

- Generator fuel

Scope 2 – Indirect emissions from purchased electricity or other purchased utilities.

Healthcare examples:

- Purchased electricity

- Purchased steam

- Purchased chilled water

- Purchased hot water

Scope 3 – Other indirect emissions that result from the organization’s business.

Healthcare examples:

- Supply chain

- Waste

- Business travel

- Employee commutes

- Patient travel

- Helicopter fuel

The Greenhouse Gas Inventory: The Basics

A GHG inventory will involve virtually every aspect of your operations, from groundskeeping and kitchens to patient floors and operating suites. The following framework makes the process more efficient and helps ensure the data collected is truly useful in developing mitigation tactics and meaningful year-over-year progress comparisons.

Setting the inventory boundary

Healthcare organizations must decide which of their facilities to include in the GHG inventory. While the ideal is to include all facilities, most of our clients begin with their main campus. Then they expand efforts to their other owned facilities, then to their leased portfolio, buildings in which the provider rents space. A phased approach can help the provider take on its biggest emitters first.

Setting these entity boundaries is an important step because it determines which emissions are scope 1 or scope 2. For example, If a fuel used to produce hot water or steam is combusted on campus or “within the boundary [within an entity’s control],” it would be considered scope 1. If the fuel was combusted off campus and that hot water or steam was purchased from an entity outside the boundary, it would be considered scope 2.

Large organizations with complex ownership structures should carefully review inventory boundaries. The GHG Protocol allows two methods of determining what should be included and excluded from the inventory: financial control or operational control. The operational control method includes all facilities for which your organization controls operations, regardless of whether you own the facilities.

The financial control method would exclude facilities that you don’t own or in which your ownership stake is less than 49%–but over which you do have operational control. Should a joint venture with another entity be included in the inventory? It depends on which boundary method you’ve chosen. If financial control, then the ownership structure of the facility is evaluated. If operational control, then the power to enact policies and governance of the facility is evaluated.

Boundaries may also be intangible. For example, emergency air flights may land on your helipad but the helicopter, its fuel, etc., is likely owned and/or managed by a third party and therefore outside operational control.

Determining the scopes and emission sources to include

Healthcare providers should be certain to include these healthcare-specific Scope 1 direct emissions:

- Medical and anesthetic gases. Anesthetic gases have a global warming potential as much as 2000 times as powerful as CO2. These gases are not absorbed by the body and are exhaled by the patient to the atmosphere. Few healthcare providers have capture systems for these used gases, resulting in nearly all becoming emissions.

- Diesel fuel. Emergency generators usually burn diesel fuel during their required frequent testing or during demand response events. However, recent regulatory changes permit the use of cleaner emergency back-up power.

- Refrigerants. Include supplies used for chillers, refrigerators, air conditioners, medical equipment, internal cooling systems, fire suppression gases, etc.

Reporting Scope 3 emissions is voluntary, but likely represents the lion’s share of any healthcare facility’s climate impact. These are the most difficult to inventory.

- Supply Chain. is especially difficult because most of the required information about emissions from third parties is not available. Given this gap in available information, the current method is to calculate supply chain emissions using a cost basis, where each dollar spent is associated with emissions factors based on expense categories.

- Patient travel. This Scope 3 emission can be challenging to capture. Zip code data, number of visits, and assumptions about modes of travel are made to calculate likely associated emissions.

- Commuting. Capturing employee commutes requires a provider to conduct an annual commuter survey, at a minimum, to estimate total employee commute emissions. More comprehensive data can sometimes be captured via parking platforms and transportation demand management programs.

- Waste. Waste-related emissions are diverse and capturing the relevant data requires the provider to be actively tracking and monitoring its waste streams. M+WasteCare is a free calculator tool that helps identify the environmental effects of waste stream disposal decisions.

Establishing the inventory baseline year

The inventory is an annual process so setting a baseline year enables organizations to measure progress. Note that the HHS pledge requires baseline years to be no earlier than 2008.

First, decide whether to use your fiscal or calendar year. Then find the oldest year for which you have complete energy data. That should become the baseline year. For some organizations, that means they can inventory just one year. Others may be able to go back several years to find a baseline.

Gathering the data

The GHG inventory involves time and resources across your institution. Cooperation and collaboration are critical and asking the right questions of the right people the first time vs. making repeated queries is one way to accomplish that. Attention to detail and quality also is essential when collecting data, and organizations likely will face a variety of challenges throughout that process, such as those in the examples below.

For instance, when gathering data about your vehicle fleet, it’s crucial to collect the vehicle model year, not just make and model. The year matters when it comes to calculating the vehicles’ emissions. A data request sheet designed to capture granular details like these in every department helps streamline the process. Consider changing departmental data gathering and retention processes, such as keeping model years and fuel records for fleets if that was not done previously and tracking energy use in ENERGY STAR Portfolio Manager.

The leaders of the inventory may need to be data detectives to find out where information is or who knows it. The person who changes out the refrigerant in the HVAC system may be the best or only source of that data. When vehicle fleets are controlled by departments, a central resource for fleet data may not exist. Procurement data can be an important source of GHG data but can be challenging to interpret. To take just one example, when gathering data about anesthetic gases, it’s important to note the size and not just the number of vials purchased.

Creating value from the inventory data

Many organizations turn to third parties to transform their raw data into usable emissions information because of the complexity of the calculations and volume of data involved. Whether done in-house or by a consultant, adhering to the GHG Protocol processes is important. This helps ensure meaningful results that are truly helpful in shaping climate mitigation and adaptation strategies. An annual report can detail the findings and provide a summary of the organization’s emissions. However, a dynamic dashboard, enabling the healthcare organization to adjust variables and see resulting effects, such as energy cost changes, can be an important aid in deciding which emission sources to tackle and how.

The inventory can also help build engagement among stakeholders throughout an organization for launching and sustaining a decarb strategy. A starting point is to understand your buildings’ energy use intensity (EUI) by dividing a building’s total energy used in one year by the building’s total gross floor area. Compare those results against established benchmarks to get a sense of the work ahead for your organization. ENERGY STAR Portfolio Manager is a free tool that can help you both calculate your facility’s EUI and benchmark your results.

And do start. Climate mitigation efforts clearly align with the healthcare industry’s core mission to protect human health. A GHG inventory will show what emissions to address, then provide hard evidence about how those strategies are working, making the inventory an essential business management and climate impact mitigation tool.

Interested in what you see? Subscribe to receive monthly news and information

more tailored to what you need.